Since

the COVID-19 outbreak emerged in the U.S., federal guidance and state orders

have been released in waves over the last several months having an especially

drastic effect on healthcare that extends beyond the care of patients infected

with the virus. Many states have now mandated the suspension of elective

medical services. When response efforts are locally executed and state managed,

however, disparities emerge over what governments consider to be “elective”. As

a result, while many healthcare services have remained uninterrupted, surgical

abortions are being called into question as to whether they should be

considered “elective,” and therefore suspended during this time.

What

is an essential business?

On

March 16, 2020, the President and the Coronavirus Task Force recommended that

civilians work from home while calling for those who work in critical

infrastructure industries to remain in operation. The “Essential Critical

Infrastructure Workforce” advisory list was developed to help state officials

determine which businesses and services should remain operational during this

period.

State

interpretations

To

create capacity and meet the increases in resource demands, many states have

chosen to follow CDC guidelines stating that “healthcare

facilities and clinicians should prioritize urgent and emergency visits and

procedures…”

In

states where surgical abortion procedures were previously facing challenges,

the term “elective” in these materials has given states significant latitude in

determining what patients need, under what terms, and when. The argument for

restricting elective or non-urgent medical procedures is not without merit. The

U.S. is experiencing a shortage of personal protective equipment and medical

supplies leaving states to ration existing provisions. Most states have required

providers to suspend non-urgent services such as annual physicals, dental

check-ups, cosmetic procedures, and routine screenings such as colonoscopies

and mammograms.

Although a patient may choose to receive an abortion, relying on this choice to classify surgical abortions as elective results in unique issues unfaced by other elective-designated medical procedures. Abortions are time sensitive. Most acutely in states that have reduced the window of time a patient may obtain an abortion, requiring a patient to wait until after the outbreak jeopardizes the opportunity they have to access this service. This is especially challenging when states are consistently moving back the date upon which elective or nonessential medical services can be resumed as new information emerges on the severity of state outbreaks. Historically, we know that restricting access to surgical abortions does not decrease the need for their services. Women who are unable to obtain an abortion will either require complex surgical procedures for later-term abortions, remain pregnant and require prenatal care and delivery services, or may use dangerous methods to induce an abortion on their own (UCSF Bixby Center). The side effects of suspending surgical abortions would result in more frequent clinical visits (i.e. prenatal care) or longer admissions (i.e. later-term abortions, self-induction, delivery) in the hardest hit clinical settings these restrictions are trying to protect. If suspending elective medical procedures is also a tactic to reduce social contact among patients and with medical providers, restricting abortions will likely result in women traveling to other states where the service is preserved, increasing the chance for viral mobility and exposure.

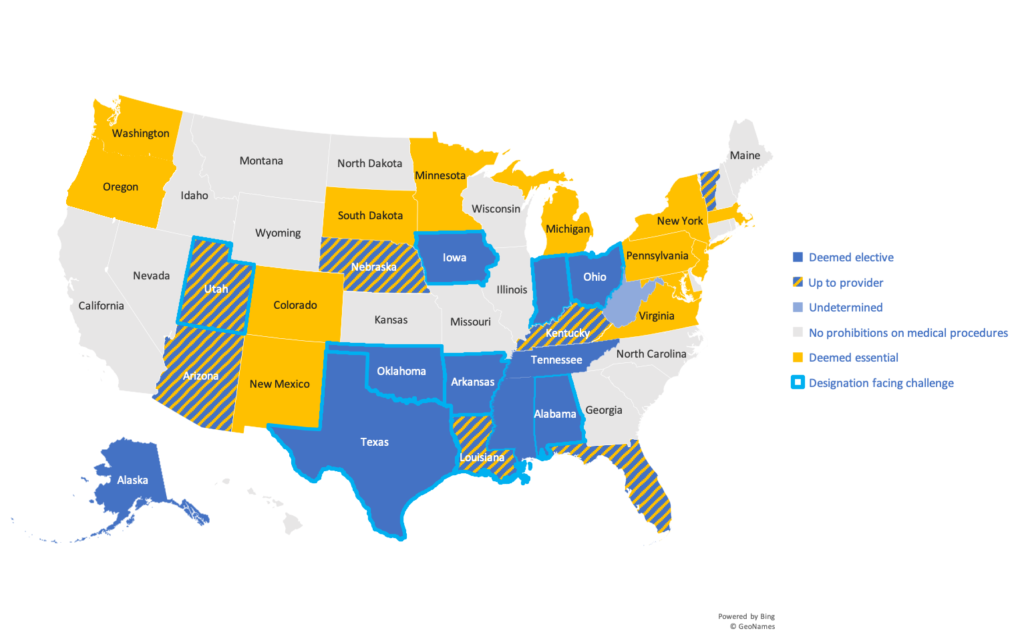

Below

is a summary of the states that have classified abortions as “elective” during

the pandemic and states that are facing challenges to these determinations in

court.

Additional

information on state-specific mandates/guidance can be found here. Challenges to these

designations in court have been summarized here.

Post-pandemic

The

COVID-19 outbreak has illuminated many vulnerabilities in our healthcare

system. Prior to the pandemic, abortion services were facing renewed challenges

in courts. Classifying abortions as “elective”, however, perpetuates the

rhetoric that abortions are chosen luxuries when women often face little choice

in the nonmedical reasons they have to obtain an abortion. It is difficult to

see through the thicket of disparate recommendations and orders made by state

and local governments, but it is clear that the end of the pandemic will not

eliminate the challenges raised by these regulations nor the discretion states

may take in the future in deeming what is and is not essential medical care.